The Arctic, Country by Country Laura Neilson Bonikowsky October 4, 2012

The Arctic, country by country

Our eight-country primer takes you to each of the council’s member states and offers a breakdown of their Arctic territory, interests and claims.

By Laura Neilson Bonikowsky

CANADA

Area: 9,984,670 sq km

Population: 34,476,688 (2012)

Canada’s frigid Arctic is definitely something to get hot and bothered about. It makes up more than 40 percent of the country’s land mass; is home to 100,000 Canadians, 80 percent of whom are indigenous peoples; and the Arctic coastline comprises nearly 75 percent of Canada’s total 243,000 kilometre shoreline, including the shores of some 36,000 islands. Canada’s closest point to the North Pole is Cape Columbia, Ellesmere Island, 769 kilometres from the pole. So closely is Canada aligned with the image of snow and ice in the global perspective that we could consider the Arctic landscape as the representative face of Canada.

The Arctic Ocean, at 14,056 million square kilometres, is the smallest of the world’s oceans. Three-quarters of its coastline belongs to Canada and Russia, with each owning territory along the Arctic straits, which, increasingly, are becoming ice-free. According to international law, no country owns the Arctic Ocean or the geographic North Pole. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982), countries bordering the Arctic are entitled to the traditional 200 nautical mile economic zone from their coastlines. Canada asserts that the Arctic Archipelago, including the Northwest Passage, comprises internal waters, basing its claim on proximity and history. Canada’s original claim to the North lies in the 1670 charter by which Charles II gave Rupert’s Land to the Hudson’s Bay Company. The area that is now the Northwest Territories and Nunavut was added in 1821. At the time, Great Britain and Russia were the big players in the Arctic and their 1825 Boundary Treaty established the boundary between what is now Alaska and the Yukon along the 141st W meridian and as far as “the Frozen Ocean.” That treaty is important to Canada’s claim in the Arctic. The United States rejects the use of the 1825 treaty; Russia sold Alaska to the U.S. in 1867.

In 1870, the Hudson’s Bay Company transferred its title to the Dominion of Canada. A decade later Britain transferred to Canada the rest of its Arctic possessions, dubiously including “all Islands adjacent to any such territories” discovered or not. Canada seemed disinterested, waiting until 1895 to pass an order-in-council accepting the transfer, and only sporadically undertook ventures to secure Arctic sovereignty, sending explorers such as Joseph-Elzéar Bernier (1904 to 1911) and Vilhjalmur Stefansson (1906 to 1918) to leave plaques or cairns and raise flags on several islands, including Ellesmere and Melville.

The first real assertion of Canadian sovereignty came in 1903 with a North West Mounted Police post on Herschel Island. Later, the RCMP operated a post office on Bache Peninsula, although no one lived near it; despite once-a-year mail delivery, the operation of a post office was proof of sovereignty. In 1926, Canada established the Arctic Islands Game Preserve, asserting the protection of the natural environment as affirmation of authority.

Canada’s claim of Arctic sovereignty has largely been predicated on cost, with expenditure justified by what is present to be protected. Culture, national identity, infrastructure development and the environment have featured insignificantly in our actions. The Macdonald government of the 1880s considered the Arctic “worthless” but we know now that is not true. What is at stake in the current drive to establish sovereignty over the Arctic is the potential for ice-free shipping routes — sea lanes created by climate change — as well as significant natural resources, especially oil and gas. The Northwest Territories’ Mackenzie Gas project alone holds 81 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and seven billion barrels of oil. Nunavut is estimated to hold a quarter of Canada’s conventional oil reserves and, in the eastern Arctic near Baffin Island, the oil potential is estimated at 10 to 30 billion barrels. Besides energy resources, the North is rich in mineral resources and their development is vital to the northern economy. The diamond industry is lucrative, with production of $2.1 billion in 2011. Minerals extracted from Canada’s north include copper, zinc-silver, tungsten, gold and nickel; metals sought in the north include rare earth elements, cobalt, and the platinum group elements. It is the search for energy resources that should concern humanity the most, for the sake of sovereignty and security, but mostly for the plight of our environment.

RUSSIA

Area: 17,098,242 sq km

Population: 141,930,000 (2012)

Russia takes its presence in the Arctic seriously. Its Arctic boundary is 24,140 kilometre long and its closest point to the North Pole is Cape Fligely, Rudolf Island, 911 kilometre from the pole. Russia claims the Northern Sea Route (also known as the Northeast Passage), a claim contested by the United States, which considers it an international route.

Arctic security, potential shipping routes and energy resources concern Russia. Gas and oil reserves would be a valuable political tool for Russia in the European energy market. Moscow estimates there are a billion barrels of oil in the Trebs and Titov deposits alone. Russia is working toward developing its oil and natural gas reserves, of which 70 percent are in the country’s continental shelf.

Historically, Russia’s Arctic focus has been the region within its landmass, but it once owned Alaska. In 1859, financially challenged after the Crimean War with Great Britain, Russia offered to sell Alaska to the U.S., fearing Alaska’s proximity to a British colony would make it difficult to defend in another war against Britain. The Alaska Purchase was delayed by the American Civil War but in 1867, the U.S. bought Alaska for $7.2 million.

In the 1930s, a growing fleet of Soviet icebreakers worked at opening the Arctic. The Sedov established a polar station on Frantz Josef Land, creating the world’s northernmost settlement, and a second station was established near the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Two non-stop crossings of the passage were made, northward in 1932 and in 1933 from Murmansk to the Pacific.

In 1937, the Soviet Union established a North Pole drifting station on a large ice floe. It was established and resupplied by several aircraft and manned by four brave explorers — Ivan Papanin, Peter Shirshov, Evgeny Fedorov and Ernest Krenkel. They took measurements, collected water and seabed soil samples, and made meteorological observations while their icy camp drifted for 274 days across 2,600 kilometre from the North Pole to the Greenland Sea before the station was evacuated by an icebreaker. The researchers disproved the common perception of a lifeless Arctic and proved that there are no landmasses or islands at the North Pole. Their polar weather observations made possible today’s routine air routes across the Arctic.

Unknown to the West, the Soviets established a second drifting station — North Pole-2 — in 1950, which determined that more observation of the Arctic was required. Arctic studies continued until North Pole-31 was terminated in 1991. During that time, 88 polar crews worked on the floating stations, drifting nearly 170,000 kilometre. The value of the information gained was unequalled in the 20th Century, and the drifting stations were taken up once more when North Pole-32 was established in 2003.

In 2001, Russia filed a formal claim to UNCLOS for 1.2 million square kilometres along the Lomonosov and Mendeleev ridges to the North Pole. In 2007, after the UN refused the claim, Russia staked a symbolic claim to the Arctic by dropping a canister containing the Russian flag on the ocean floor from a submarine at the geographic North Pole, declaring, “The Arctic is ours, and we should demonstrate our presence.” Though a creative endeavour, such symbolic acts are insufficient proof of sovereignty under international law.

Russia began increasing its Arctic military presence in 2007. Shortly after the flag was ”planted,” then-president Vladimir Putin ordered the resumption of regular air patrols over the Arctic Ocean and the Russian Navy expanded its presence for the first time since the Cold War (United States Strategic Studies Institute). In July 2011, Russia began undersea mapping of the continental shelf and Putin announced the country’s willingness to negotiate with its Arctic neighbours, adding “of course we will defend our own geopolitical interests firmly and consistently.” Defence was clear in Moscow’s decision to build six icebreakers and commit $33 billion to constructing a year-round Arctic port. Russia’s Arctic region contains vast mineral wealth, including nickel, copper, coal, gold, uranium, tungsten and diamonds.

In 2010, Russia and Norway concluded a 44-year dispute over the Barents Sea. Under the precedent-setting treaty, the countries will split a 175,000 square kilometre area. Estimates of reserves in the region vary, but are in the order of 4 billion barrels of oil and 878 trillion cubic feet of gas. (See Norway’s take on page 48.)

UNITED STATES

Area: 9,826,675 square km

Population: 312,780,968 (2012)

The United States’ Arctic coastline is a mere 1,706 kilometres, but the economic potential represented by Alaska is great, as is a northern presence for security and trade, although in the minds of most, Alaska barely registers as a state. The United States’ closest point to the North Pole is Point Barrow, Alaska, which is 2,078 kilometre from the pole.

The U.S. is interested in the Arctic Ocean for its sea routes and insists that the Northwest Passage is an “international strait,” citing as its precedent the criteria established by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 1949 in the Corfu Channel Case (the United Kingdom versus Albania). In 1946, in the Corfu Strait, two British destroyers hit mines in Albanian waters and sustained damage and loss of life. The matter was referred by the UN Security Council to the ICJ, which determined that the strait’s geographic situation connecting two parts of the high seas and its use for international navigation in which vessels pass within 12 nautical miles of one or more coastal states establishes a right to pass through the strait without coastal state permission. This does seem to be a relevant rationale for allowing unrestricted passage in the north.

However, the Strait of Corfu is unlike either the Northwest Passage or the Northern Sea Route, which the U.S. also argues is an international marine thoroughfare. The northern routes comprise multiple passages between islands, each of which has complex topographical and environmental concerns. On two occasions, the U.S. sent surface vessels through the Northwest Passage without asking Canada’s consent: the SS Manhattan, an icebreaking super-tanker, in 1969, and the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Polar Sea in 1985. Most Canadian specialists argue that these two transits are insufficient to fulfill the “used for international navigation” criterion. American analysts respond that the ICJ did not specify a threshold, and some of them argue that prospective use is enough.

In 1945, the United States claimed jurisdiction over the natural resources of its continental shelf beyond its territorial limits; other nations quickly followed suit. In 1967, to satisfy the need for changes to the law of the seas, the United Nations undertook a conference comprising a series of sessions spanning 15 years to produce a comprehensive set of laws known as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS. The convention became effective on Nov. 16, 1982, and recognizes a nation’s sovereignty over natural resources within 200 nautical miles and allows territorial claims up to 350 nautical miles from shore provided the country can prove that its continental shelf extends beyond the 200-mile limit. There is nothing in the convention to compel the Arctic countries to accept the UN’s rulings on competing claims. UNCLOS has 160 member countries; the United States is not one of them, though the other Arctic countries are. The U.S. disagrees with Part XI of UNCLOS, which deals with minerals found on the seabed of the Exclusive Economic Zone (within the 200-mile limit), although it has agreed to UNCLOS provisions relating to fisheries.

The U.S. pursues its claims “as an independent, sovereign nation,” relying partly on President Harry Truman’s proclamation that any hydrocarbons or other resources discovered beneath the American continental shelf is the property of the United States. The country can defend its claims through bilateral negotiations and in multilateral venues such as the 2008 Arctic Ocean Conference in Greenland, but it must determine how far into the Arctic Ocean its continental shelf extends. Canada realizes that cooperation between the two countries would be mutually beneficial for development of northern gas reserves as well as energy and national security and defence (eg, NORAD). The NORAD Region in Alaska has regained its former relevance with Russia’s increased military presence in the Arctic.

Natural resources are vital to Alaska’s economy and to the U.S. economy overall. In addition to oil and gas, Alaska’s resources include timber, fish, coal, gold, diamonds, mercury, platinum and copper. The state’s oil potential is huge; the North Slope alone holds roughly 100 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Alaska’s natural gas potential is estimated to be more than 200 trillion cubic feet, with roughly 163 trillion cubic feet of that in the North Slope.

DENMARK

Area (continental): 43,098 sq km

Greenland area: 2,166,086 sq km

Population (continental): 5,584,758 (2012)

Population Greenland: 57,695 (July 2011 est.)

Denmark is a tiny Scandinavian monarchy well south of the Arctic Circle; continental Denmark is not considered part of the North, but its colonial territory, Greenland, gives the country a role in the Arctic sovereignty dispute. Denmark’s closest point to the North Pole is Kaffeklubben Island, Perry Land, 707 kilometres from the pole. Denmark’s interests, like those of the Arctic countries, lie in exploiting energy resources and increasing trade routes. Using the Northern Sea Route instead of the Suez Canal would cut 7,000 kilometres off the trip from Rotterdam to Tokyo, saving both time and fuel costs.

Denmark was once a European super-power with influence as great as that of the largest European nations. In fact, it ruled England from 1015 to 1034 and established colonies in the Caribbean in the 17th Century. Its current size and influence is “the result of 400 years of forced relinquishments of land, surrenders and lost battles,” according to its official website. Denmark’s association with Greenland reaches back to the explorations of the Norse, who established colonies on the island in the 10th Century. The Norse colonies disappeared in the 15th Century and Greenland remained under the rule of the joint kingdom of Denmark-Norway, which existed from 1536 to 1814. It became a colony of Denmark in 1814 and in 1953, it became part of the Commonwealth of the Realm of Denmark. In 1979, Denmark granted Greenland home rule and, in 2009, Greenland became an autonomous territory, with power transferred from the monarchical government to the local government.

Denmark has only recently begun to make claims to the Arctic, jumping into the fray with the other members of the “Arctic Five” (Canada, Russia, Norway and the United States), arguing that the Lomonosov Ridge — the same ridge Russia claims — is an extension of Greenland. Norway contests the claim and Canada has also claimed the ridge (in 2010).

The ridge is a towering fold in the ocean floor. It crosses the Arctic Ocean from the continental margin of North America between Greenland and Ellesmere Island and continues nearly 1,800 kilometres past the geographic North Pole to the continental edge of Russia in the Laptev Sea. On the North American side, there is a wide plateau and, on the Siberian side, the ridge breaks into other ridges. Near the pole, the ridge appears as a block splintered into a series of high and low points. Surveys of the ridge have amassed an array of data that includes the depth of silt across the Arctic shallows to the composition of rock 4,000 metres beneath the ocean’s surface. The ridge’s geological origins are less clear; it is likely that each claim will be proven correct to some extent.

In addition to the Lomonosov Ridge, Denmark and Canada both claim ownership of Hans Island (part of Nunavut, according to Canada), a mere speck in the oceans of dispute over Arctic sovereignty. It is a tiny (1.3 square kilometres) unpopulated island in the Kennedy Channel between Ellesmere Island and Greenland. It was discovered in 1871 by American explorer Charles Francis Hall, who named it for his guide, Hans Hendrik. Denmark claims the island is geologically part of Greenland and is closer to Greenland than to Ellesmere Island. Canada argues that the claim has lapsed because Denmark has not enforced sovereignty over it. Cartographers from both countries depict it as part of their respective countries. The seabed surrounding the island has oil and the island offers a staging point for offshore rigs. In 1971, Canada and Denmark signed a treaty delimiting the island’s continental shelf and since have taken turns planting flags, leaving bottles of their own countries’ alcohol (schnapps for Denmark, Canadian Club for Canada), and running military exercises, continuing the 30-year dispute that negotiators said in 2011 was nearing a resolution.

Denmark presented its “Arctic Strategy” to the UN in August 2011, ratifying UNCLOS and outlining its intention to claim the North Pole seabed by 2014. Its Arctic priorities lie in its control of Greenland’s foreign affairs, security and financial policy, including its Exclusive Economic Zone, in consultation with the home rule government of Greenland. Denmark also owns the rights to the majority of Greenland’s strategic resources — gold, diamonds, natural gas and oil and iceberg water, which is very much in demand as bottled water.

SWEDEN

Area: 450,295 sq km

Population: 9,507,324 (2012)

Sweden is the third-largest country in the European Union and a constitutional monarchy. Only a small portion of its northern region lies above the Arctic Circle. Its most northerly point is roughly 2,000 kilometres from the North Pole. The Arctic region — Lapland — is inhabited by the indigenous Sámi, whose total population of roughly 70,000 is spread across Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia. Like continental Denmark and Finland, Sweden does not have an Arctic coastline but it is a nation closely tied to the sea by its geographic connection to the Gulf of Bothnia, the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean and would benefit from access to trade routes in the Arctic Ocean. The country is a leader in ice-breaking operations and can support commercial traffic in the Arctic.

What is now Sweden was once covered by a thick ice cap; as it retreated, people migrated into the region and eventually an agrarian society was established. Sweden launched incursions into the sea during its Viking Age (800 to 1050), creating trade links with the Byzantine Empire and the Arab kingdoms. In 1280, King Magnus Ladulas established the nobility and a society based on the feudal model. In the 14th Century, the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden were joined in the Kalmar Union under the rule of the Danish Queen Margareta. The union lasted from 1397 to 1521 and was marked by violent internal conflicts such as the “Stockholm Bloodbath” in 1520 during which 80 Swedish nobles were executed. After the dissolution of the Kalmar Union, Sweden engaged in several wars with Denmark and became a great power in northern Europe. It even founded a colony in North America, at what is now Delaware; however the colony was short-lived. As an agrarian nation, Sweden could not maintain its powerful position for long.

After its defeat in the Great Northern War (1700 to 1702) against the combined forces of Russia, Poland and Denmark, Sweden lost most of its possessions on the Baltic Sea and was reduced to what is now Sweden and Finland. During the Napoleonic Wars, Finland was surrendered to Russia, but French marshal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, elected heir to the Swedish throne in 1810, forced Norway into a union with Sweden in 1814 as compensation. That union was dissolved in 1905 after several internal disputes. Sweden has not been involved in a war since the brief war with Norway in 1814 and since the First World War has pursued a policy of non-alignment in peacetime and neutrality in wartime. Its security is based on strong national defence.

Sweden feels its ties to the Arctic deeply. The country’s research into the changing Arctic climate is of long standing; some of its measurement case studies reach back 100 years, such as environmental monitoring of temperature, precipitation, ice-thaw, flora and fauna. Sweden has contributed to the global understanding of climate change and continues to analyze levels of known and new hazardous substances in the fragile Arctic environment. In addition, Sweden is the site of research facilities, such as the Abisko Scientific Research Station, that administers, coordinates and conducts tests for researchers around the world. The Tarfala Research Station, in the Kebnekaise Mountains, conducts glacier monitoring, meteorological and hydrological analyses and snow chemistry and permafrost studies.

Sweden was one of the founding members of the international cooperative body on Arctic matters.

It launched its official Arctic strategy in May 2011, the last of the eight Arctic states, in response to growing international pressure and domestic calls to do so. At the same time, Sweden took on chairmanship of the Arctic Council, a position it will hold until 2013 when Canada takes over. The strategy document lists Sweden’s priorities in the Arctic as being related to “business and economic interests in (the free trade area of) the Arctic and Barents Region” as well as “mining, petroleum and forestry; land transport and infrastructure; maritime security and the environmental impact of shipping; sea and air rescue; ice-breaking; energy; tourism; reindeer husbandry” and other endeavours such as information and communications technology and space technology. But its first level of concern in the Arctic comprises facilitating multilateral cooperation; the environment and sustainable development; and the human dimension, particularly indigenous cultures of the North.

ICELAND

Area: 103,000 sq km

Population: 319,575 (2012)

Iceland is a Northern European island nation situated northwest of the United Kingdom between the Greenland Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, on the fringe of the Arctic Ocean. Its closest point to the North Pole is Kolbeinsey, Eyjafjorour, which is 2,552 kilometres from the pole. Iceland’s interior is uninhabitable due to a volcanic mountain plateau of glaciers, lava fields and desert, but the coastal areas provide land for grazing and cultivation. The country has the highest literacy rate in the world.

Iceland was first settled by renegade Norwegian chieftains and their followers in the 9th and 10th centuries. Icelandic culture is based on these early Viking settlements and it was this era that saw the first association between Iceland and what is now Canada. About 985 or 986, an Icelandic flotilla led by Eric the Red set out to colonize southwest Greenland. A trader, Brjarni Herjolfsson, belatedly sailed to join them but was blown off course. He became the first European verified to have reached the North American mainland. His first sighting of land was probably Newfoundland, from which he coasted north. The more southerly lands he found were well forested. In 1000, Leif Ericsson organized an expedition to explore sections of the North American coast discovered by Herjolfsson. Ericsson established a base camp in an area he called “Vinland,” Land of Wine, because of its wild grapes. Vinland, according to archaeological evidence, was probably the coastline of the Gulf of St Lawrence.

Iceland has the world’s longest standing legislative assembly, the Althingi, which was established in 930 and, despite changes in its role over the centuries, remains as the country’s legislature today. The country was independent for more than 300 years before internal struggles let to it coming under the rule of Norway in 1262. The Althingi continued at this point, with the adoption of the Old Covenant, but its function changed to granting consent to the executive power of the king.

Iceland became a possession of the Kalmar Union (1397 to 1521) when the kingdoms of Norway, Denmark and Sweden were united. When absolute monarchy was established in Denmark in 1662, the Althingi served a judicial function until 1800 when a royal decree demanded its abolition and its responsibilities were assumed by a high court. Iceland remained a Danish dependency when the joint kingdom of Denmark-Norway dissolved in 1814. Another royal decree resurrected the Althingi in 1843. Its role underwent several changes until it regained legislative power in 1874, when Iceland gained limited autonomy from Denmark; it attained complete independence in 1944.

In 1875, the Askja volcano erupted and the subsequent fallout devastated the economy and caused extensive famine. In the next 25 years, 20 percent of the country’s population emigrated, mainly to Canada, especially Manitoba, and the U.S. Icelanders had been coming to Canada since 1873; they established a colony known as New Iceland (now Gimli) on the shores of Lake Winnipeg. Manitoba was at the time an unorganized part of the Northwest Territories and a reserve was set aside by an order-in-council that allowed New Iceland settlers to create their own laws and maintain their own schools. A series of natural disasters decimated the population, initiating an exodus to Winnipeg and North Dakota that began in 1878.

Iceland’s role in determining Arctic sovereignty is complex. It is a member of the Arctic Council with Canada, Russia, the U.S., Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland. The European Union believes Iceland will provide it with influence over the Arctic and its resources, giving the EU a “voice in the Arctic and the North Atlantic dimension of the Union’s external policies.” Canada has protested any formal involvement in the Arctic by the EU, including participation as an observer, citing Europe’s lack of understanding about recognizing North Atlantic and Arctic heritage and the livelihoods of northern nations. Iceland is not counted among the coastal nations (the “Arctic Five” comprises Canada, Russia, the U.S., Denmark and Norway). The Icelandic government protested its exclusion from the group and a resolution passed by the Althingi in 2011 reinforced Iceland’s commitment to having an active role among the coastal nations. The question to be answered is whether Iceland or the European Union will become the coastal state.

NORWAY

Area: 385,199 sq km

Population: 4,950,000 (2012)

Norway is a constitutional monarchy in Northern Europe. Its nearest point to the North Pole is Rossoya Sjuoyane (Ross Island), Svalbard, 1,024 kilometres from the pole. Norway’s history, like that of other Scandinavian countries, involves Vikings, who settled in the Orkney Isles, the Shetlands and Hebrides, the Isle of Man and the north of mainland Scotland and Ireland. Dublin, which was founded by Vikings in the 9th Century, was under Norse rule until 1171.The Viking Age ended in 1066, when Norwegian King Harald Hardruler and his men were defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in England.

The late Middle Ages in Norway were marked by economic decline. The plague and other epidemics decimated the population during the 14th Century. Economic depression brought political consequences; Denmark’s power was increasing. Lands and property passed into foreign hands, the Norwegian nobility shrank and Norway’s ability to assert itself diminished. A union between Norway and Denmark was enforced by treaty from 1450 and by 1536 Norway was no longer an independent kingdom.

In 1813, at the Battle of Leipzing, Napoleon suffered a crushing defeat; among his opponents was the Kingdom of Sweden, which wanted Norway as a safeguard on its western border. Sweden’s allies had promised it could have Norway as a spoil of war. In January 1814, Danish King

Frederick VI surrendered, severed his ties with Napoleon, and gave Norway to Sweden, ending the four-centuries-long union of Norway and Denmark. Norway refused the cession of their country to Sweden and adopted a new constitution. Sweden invaded Norway but agreed that Norway could keep its constitution in exchange for accepting union under a Swedish king. King Frederick relinquished his power on Oct. 10, 1814.

Increasing nationalism through the 19th Century led to a referendum in 1905 that granted Norway its independence. During the First World War, Norway remained neutral but suffered heavy shipping losses due to the submarine war and mining of the seas. The war yielded financial gains, however, and Norway was able to recoup major companies that had passed into foreign ownership. At the outset of the Second World War, Norway again proclaimed its neutrality but was occupied by the Nazis for five years, resulting in German exploitation of the Norwegian economy and mass executions. In 1949, Norway joined NATO. During the 1960s, the discovery of oil and gas in adjacent waters improved the country’s economy. Norway rejected joining the European Union in referenda held in 1972 and 1994.

Norway’s presence in the Arctic is considerable and not restricted to its own territories. Canada was the site of many of Norway’s Arctic achievements. Between 1898 and 1902, the intrepid Otto Sverdrup became known for his expedition to the area of Ellesmere Island. In the course of four winters in the ice, he discovered several islands west of Ellesmere and mapped large portions of the high Arctic. He became the first person to set foot on the islands of Axel Heilberg, Ellef Ringnes and Amund Ringnes; even the Inuit had not visited them. Sverdrup claimed them for Norway. The claim was abandoned in 1931, and Canada paid Norway $67,000 for Sverdrup’s records.

Norwegian Roald Amundsen was the first to sail through the Northwest Passage, in 1906, a feat that had eluded sailors for three centuries. Amundsen set sail in his sturdy vessel the Gjøa, equipped with sails and a 13 horse-power motor and manned by a crew of six, sailed from the Oslo Fjord through the ice-laden waters of the passage. Along the way, they compiled a wealth of scientific data, the most important of which concerned earth’s magnetism and the exact location of the magnetic North Pole. Amundsen also led a successful expedition to the South Pole.

Norway’s role in the Arctic, and therefore its place in the Arctic sovereignty discussions, is vital to its economy. Its second-most important resource, after hydropower, is petroleum from the continental shelf, which is estimated at 13.2 billion standard cubic metres of recoverable oil equivalents. Partly because of its ability to exploit its energy resources, and partly because of its ability to invest and save (via the Petroleum Fund), Norway posted a government budget surplus in 2011 that was equal to 13.6 percent of its gross domestic product.

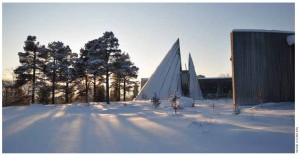

A view from Saana in the municipality of Enontekiö in Lapland, Finland. The stone stacks were created by visitors to Saana.

FINLAND

Area: 338,144 sq km

Population: 5,402,758 (2012)

Finland is a Northern European country bordered by Sweden, Norway and Russia. Like Sweden and continental Denmark, Finland is not bordered by the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic Circle crosses it about a third of the way south from its most northern point, neighbouring on Norway, which is roughly 1,700 kilometres from the North Pole. Finland’s Arctic region — Lapland — is inhabited mainly by the Sámi.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Finland was first settled during the Stone Age, around 8,500 BC, by itinerant hunter-gatherers. The origin of the Finnish people is unclear, but many scholars suggest they originated in what is now west-central

Siberia. Swedish kings established their rule in the 12th Century. During the Swedish era, which lasted into the 19th Century, Finland was a province and then a grand duchy. This included a time of enlightenment; the first literature written in Finnish was published and the first university in Finland was established. Finish people comprised a significant portion of the first Swedish settlers in North America in the 17th Century. During the 18th Century, Finland was occupied twice by the warring forces of Sweden and Russia.

Finland became an autonomous grand duchy of Russia in 1809 after being overrun by the armies of Alexander I in the Finnish War. In 1835, the Finnish national epic, The Kalevala, a collection of mythology and legends, was published, stirring feelings of nationalism. From the 1860s, a nationalist movement grew in Finland and it won its independence in 1917 after the February Revolution and the October Revolution. During the Second World War, Finland successfully defended itself against the Soviet Union, though with some loss of territory, and subsequently signed an armistice with the USSR before forcing the Germans out of northern Finland.

In the 50 years after the war, Finland transformed itself from a farm and forest economy to a diversified modern industrial economy. It has been a member of the European Union since 1995 and was the only Nordic state to adopt the Euro when it was initiated in 1999.

Located on the taiga belt, Finland’s hydrocarbon resources are limited to peat and wood; it has no domestic sources of fossil energy and must import crude oil, mainly from Russia, as well as petroleum and natural gas. Finland operates several refineries and has an extensive pipeline system. It exports heavy fuel oil, light fuel oil, gasoline and diesel oil. Therefore, transportation of energy resources from the Arctic region to Europe and beyond is among Finland’s significant economic, political and security interests in the region. Finland has sizeable investments in the Barents Region, and the oil and gas reserves of both Norway and Russia offer opportunities for Finnish companies in the areas of offshore industries and shipbuilding, establishing infrastructure, building machinery and equipment, and providing logistics. The largest known Arctic deposits of oil and gas that will most likely be exploited first are located in the northern parts of the Yamal Peninsula and the Shtokman and Fedinski fields in the Barents Sea.

One of Finland’s stocks in trade is its knowledge about the Arctic. The country’s expertise and research about the Arctic are internationally recognized and Finland has played an important role in presenting initiatives on Arctic issues. It also belongs to most organizations and treaties concerning the North.

Finland’s goals in establishing an Arctic strategy are to strengthen its role as an international expert in the Arctic by investing in education, research, testing, technology and product development; to make better use of Finnish experience in winter shipping and Arctic technology in Arctic sea transport and shipbuilding; and to improve the opportunities of Finnish companies to benefit from their Arctic knowledge in the large projects undertaken in the Barents region by supporting the networking, export promotion and internationalisation of small and medium-sized enterprises.

In 2011, Finland initiated political and economic ties with Russia in the Arctic. Finland has a long history of building vessels capable of withstanding the rigours of the Arctic Ocean for the Soviet Union and later for Russia. Finland built two nuclear-powered icebreakers for Russia, the Taimyr and the Valgash, in the 1980s, as well as the deep-water submarine used by explorer Arthur Chilingarov when he “planted” the Russian flag on the North Pole seabed in 2007.

Laura Neilson Bonikowsky is a writer from Alberta.

Comments

Post a Comment